- Home

- Julia Lawrinson

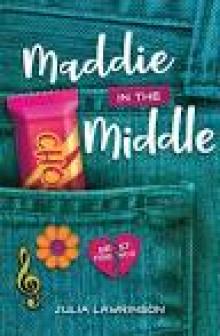

Maddie in the Middle Page 10

Maddie in the Middle Read online

Page 10

Then the principal calls, ‘Maddie! Come in!’

‘Well,’ the principal says, once we’ve closed the door behind us. ‘What’s going on, Maddie?’

And in a small voice, I tell him.

The last place I want to go, after seeing the shock on the principal’s face, is assembly. I can’t bear the happy chatter, the chirpy discussions, seeing Katy – my friend who would never steal anything, no matter how good the reason – performing her head councillor duties, the school motto emblazoned behind her head. But I have to go.

And at least I will definitely see Samara. Even if I don’t get to talk to her, I am sure that if I see her, I’ll somehow feel a bit better.

‘Happy Monday, everyone!’ Katy says. ‘I hope everyone is ready for more amazing achievements this term. I have some announcements …’

I sit at the back of my class. I peer around, but I can’t see Samara anywhere. I try to spot Dayna with the little kids, or Tom, jiggling around like he usually does, but I can’t see any of them. I fiddle with the hem of my skirt, and edge out of the gym when assembly is over, as far away from Katy as I can.

At recess, I slink around the edges of the quadrangle. Brooke offers for me to sit with her group, but I make out that I am looking for Mrs C. I see Elsa, Jordi and Grace, but Samara isn’t with them. Katy is with Lia, and she shoots me a puzzled look.

At lunch, I ask to stay in the classroom, saying I have a stomach ache. Which is true enough.

After lunch, it is time for creative writing. Normally, I love writing. But today I don’t know how anything will come from the sludge of misery I feel. The topic Mrs L draws out of the box is ‘sunshine’.

I groan. Katy turns and gives me a look.

‘Is everything all right, Maddie?’ Mrs L asks.

‘Sorry,’ I say.

‘You have twenty minutes to write a piece about sunshine,’ Mrs L continues. ‘Starting from – now.’

For a moment I pause. Then I write:

There are places where the sun shines. It shines in countries I’ve never visited, full of people I’ll never meet. It shines through the classroom windows, hot in summer, pale in winter, as though something has stolen its warmth. The sun shines on those who are happy and those who can’t remember anything but sadness. It inches around the world, bright, leaving darkness behind it. But if you stare at something bathed in sunshine, when you look away all you see is a bright shadow, like an x-ray under your eyelids. If you stare at the sun for one second too long, it burns the back of your eyes. And then, everything will lose its colour. There will be nothingness, forever. It is too late to look away.

I don’t know how I will make that paragraph into a story, or something longer. But I like it, even if I don’t think Mrs L will. My words explain how I feel, just a little.

When the siren goes, I walk out to the gate. I see Samara, Tom and Dayna, together as always, turning left. I jolt out of the stupor I’ve been in all afternoon, and start to run toward them.

But I’ve only gone a few steps when Samara turns, fixing her eyes on me. She doesn’t smile, she doesn’t frown. There is no expression in her face.

As if we have never been friends.

As if we don’t know each other at all.

Of course, I tell myself on my way home, Samara can’t acknowledge me. It is too risky. Of course that’s what it is.

Tom and Dayna also pretended they hadn’t seen me. Of course, that made sense too. Samara would have told them to act cool.

It all makes sense.

It also makes me want to bend over and cry with the sudden pain in my stomach.

Couldn’t she have given me a sign? A furtive look, a hand signal, anything? We’d planned what would happen if we were caught stealing, but we never thought about how we would act after that.

Tomorrow, I decide, I will find some way of getting Samara alone. To talk to her. To make sure that we are still friends.

But after I get home, do my homework and practise my clarinet, Dad comes home. He is carrying a new outfit, a formal dress of a kind I would never normally wear.

‘Here,’ Dad said, handing the dress to me. ‘It should fit.’

‘What for?’ I ask.

‘For court,’ Dad says. ‘You get to put in a plea tomorrow, then they’ll work out what to do in a few months.’

‘What?’ I vaguely remember some mention of appearing in court, but I didn’t think I would really have to do it, and so soon. ‘But I said I did it. Why do I have to go to court?’

‘You need to tell the magistrate that,’ Dad says.

‘Is a magistrate a judge?’

Dad doesn’t answer. He just says, ‘Maddie, I have a headache. Please go to your room now, and you can heat something in the microwave for dinner, later.’

‘Okay,’ I say. Dad and I have never fought. We’ve had little arguments over what to have for dinner, or what to watch on television, but never has Dad seemed to be so angry that he can’t bear to be around me.

‘Oh, and your mother thinks that maybe you should go and live with her in Port Hedland for a while.’

‘What did you say?’

‘I said I’d think about it.’ By Dad’s tone of voice, I can tell that is the end of the conversation.

I walk numbly to my room. I unzip the cream-coloured dress. It has a high collar and long sleeves, and I feel like I am suffocating in it. I briefly think about telling my dad it doesn’t fit, but I know he would check.

Court. I am going to court, like a criminal.

That is another thing Samara and I hadn’t talked about.

I am on my own.

The wind whips up from the pavement and into my face as we make our way to the court. I need to walk fast to keep up with Dad’s long strides. He’s had to take the day off work, and he is in a bad mood – again. I want to say something to him to make him smile, or to treat me the way he used to. To be Dad and Mads, as he used to say. But there is nothing I can think of to make anything better. For him or for me.

We turn the corner toward where the court is, and I stare in fright. There is a bunch of people there with fat microphones and chunky black cameras hoisted over their shoulders. I run ahead and grab Dad’s hand. He doesn’t squeeze back, the way he normally would have, but he doesn’t let go, either.

‘What are those people doing here?’ I whisper.

‘They’re media,’ Dad reply. ‘From the television and newspapers.’

I gulp. I know stealing is bad, of course. But I hadn’t imagined this. What would everybody think, seeing me on the television news outside the court? Everybody in the school will know, not just the principal. I’d been worried about Katy finding out: I hadn’t thought about everyone else.

‘Dad, can we come back another time?’ I say.

‘No,’ Dad says. ‘If you don’t appear today, they’ll take you into juvenile detention.’

‘What’s that?’

‘Jail for young people.’

‘But I only –’

Dad stops. He turns me by the shoulders so I am facing him.

‘What you don’t seem to understand, Maddie, is that what you’ve done can’t be undone. Now you’ve done this, everything is different,’ he says. ‘People with criminal records get treated differently to other people. You are about to have a criminal record, officially.’

‘I know, but –’

‘Please,’ Dad says. ‘Do not make any excuses. It will only make me feel even worse about what you’ve done than I already do.’

His words make me shrink. He walks off ahead, and this time, I follow behind. The people with the microphones and cameras eye me as I approach. I can see myself reflected in the pale eye of a camera, a girl walking toward them, alone, guilty.

Then the mass of them begin shouting at me, moving in my direction. I put my hands in front of my face, and I can feel the vibrations from the pavement as they run toward me. Someone brushes roughly against my shoulder.

I open my

eyes.

They aren’t running toward me. They are running past me.

‘Ohhh,’ I breathe out.

I turn and see a boy a few years older than me, getting out of a car with his mother and what look like his two younger sisters. As the car drives away, the media crowd around them, surrounding them, thrusting cameras in their faces, yelling questions. The boy puts up his hand, and his mother tucks a sister under each arm. They try to look straight ahead, past the cameras.

‘Are you sorry for what you did?’

‘Do you have any words of sympathy for the family?’

‘This is your third offence. Do you think you deserve to go to detention this time?’

The boy’s face is stony. I hear his mother yell, ‘Leave him alone, it was his cousin he killed. He’s punished on the inside!’

Dad grabs my hand and pulls me toward the courthouse.

‘Quickly,’ he says, dropping my hand. ‘Before they catch up with us.’

I rush up the stairs of the salmon-coloured building that has ‘Children’s Court’ in silver letters above the entrance. I pause before the black doors, then they slide open. My heart is still pounding. I think of what they said to that boy.

He’s punished on the inside.

I know he’s done something terrible, but I feel sorry for him all the same.

Almost as sorry as I feel for myself, going into the Children’s Court for the first time.

‘Name?’ a guard says, looking down at some papers stuffed under a clipboard.

Dad looks at me, and I say my name in a small voice.

The guard runs her finger down a long list. When she finds my name, she puts a highlighter through one of the lines.

‘Courtroom One, nine fifteen,’ the guard says. ‘The duty lawyer will come and get you before that.’

I want to ask what a duty lawyer is, but before I can we are ushered through a metal detector. Dad’s wallet and keys are sent through a conveyor belt, and he retrieves them at the end, depositing them into his pockets.

On rows and rows of fixed plastic chairs are young people waiting to go into court. Most of them are boys; some look like they are almost grown up, leaning forward on their long legs, elbows on their knees, looking at the ground. Others fold their arms in front of them, or lean back, legs out, arms behind their heads, like they are sitting on a beach chair. There are two girls, older than me, with lots of makeup and wearing clothes that look like they don’t belong to them. Like me.

Dad sits down: the whole row sways and squeaks. I perch next to him.

‘Madeleine Lee?’ a woman with neat grey hair calls from one of the corridors.

Dad stands up and waves me to go in front. The woman has a kind face, but she looks at me with a direct gaze that makes me want to squirm.

‘Come this way,’ the woman says in a pleasant voice. ‘I’m afraid we call this room the cupboard, but we’ve got a very full list this morning.’

We are led into a tiny room with a small circular table and a high square window.

‘I’m Jay, Madeleine,’ the woman says.

‘You can call her Maddie,’ Dad says. ‘I’m Michael.’

The woman nods. ‘This is your first offence, isn’t it, Maddie?’ She leafs through some paperwork in front of her. ‘You were caught stealing?’

‘Yes,’ I say.

‘And it’s a representative charge.’

‘What’s that?’ Dad asks.

‘It means they have evidence you’ve done this before, but they are only charging you with the one offence,’ Jay says. ‘It makes the court take it more seriously. Otherwise, the police might have just given her a warning and sent her on her way.’

‘I see,’ Dad says.

Jay turns her gaze back to me.

‘Before I explain to you what is going to happen this morning, I’d like you tell me in your own words what happened for you to end up here.’

‘You mean, about the stealing?’

‘Please. I’ll take notes as you talk.’

‘Well,’ I say. ‘I stole some chocolates and I got caught.’

‘And did you tell the police that you’d stolen other things before?’

My cheeks turn hot.

‘Yes,’ I nod.

‘What sort of things have you stolen before?’

‘Just chocolate and things like that,’ I say.

I can feel Dad staring at me.

‘And how long have you been stealing?’

‘A couple of months,’ I whisper.

‘And has anyone else been with you?’

‘No!’ I say more loudly than I intend. ‘No, no one.’

‘What about the girl that was there?’ Dad interjects.

‘She was just … with me,’ I say, hoping I sound convincing. ‘She didn’t steal anything.’

Well, I think to myself. She didn’t get caught stealing anything …

‘And what have you been doing with the chocolate? Is it for you?’

‘I give it to … people,’ I say.

‘Do they pay you for it?’

‘No.’

‘So where did you get the idea to steal things?’

I shrug.

Jay looks at me for a while.

‘All right,’ Jay says. ‘So you’ve got your dad here with you, that’s great. Where is your mum?’

‘She lives in Port Hedland,’ Dad says. ‘We’re civil, but she’s remarried and moved with his job.’

‘But she’s involved with Maddie’s upbringing?’

‘I’m the primary caregiver,’ Dad says. ‘But yes, Stacey is involved.’

‘Okay,’ Jay says, ‘What about other family?’

‘It’s really just me and Maddie,’ Dad says. ‘My mother lives in Queensland, so Maddie sees her sometimes in the Christmas holidays. But nobody else.’

‘Okay,’ Jay says. ‘So Maddie, how would you say you do at school?’

‘All right,’ I say.

‘Do you ever get in trouble there?’

‘Never!’

‘What about friends?’ Jay asks. ‘Do you have a lot of friends?’

‘Katy’s my best friend,’ I say. ‘She’s head councillor.’

‘We haven’t seen much of her lately, though,’ Dad adds.

‘Michael, I need Maddie to answer, if that’s okay.’ Jay says. ‘What about other friends?’

I shrug. I know I can’t mention Samara.

‘I sit with Brooke and some other girls, when Katy’s busy,’ I say. ‘She’s busy a lot this year.’

Jay writes down a few things. I try to read what she is writing from upside down, but I can’t. When she’s finished, she puts her pen down and weaves her fingers together.

‘Right, Maddie,’ she says. ‘You said to the police that you wanted to plead guilty, is that correct?’

‘I did it,’ I nod.

‘You know that means that you can’t go back and change your mind, or say someone else pressured you, or anything like that?’

I frown. ‘I didn’t say anything like that.’

‘There was another girl there when you were picked up,’ Jay says. ‘Was that Katy?’

‘No,’ I say.

‘Who was it?’

‘Just another girl from school,’ I say.

Jay keeps her gaze evenly on me, until I have to look away. I have my story, and I want to tell it. I don’t want to talk about anything else.

‘All right, Maddie,’ Jay says. ‘I’m going to tell the magistrate that you’re pleading guilty. Is there anything else I can tell her?’

‘Like what?’

‘Well,’ Jay says, ‘most people feel bad when they do something they know they shouldn’t.’

‘Oh,’ I say. ‘I do. I wish I’d never stolen anything.’

‘That’s good to know,’ Jay says. ‘I will recommend to the magistrate that you are diverted to our juvenile justice program. You’ll have to meet with a justice officer every week for, say, three months, mayb

e do some community service –’

‘But I just want it to be over!’ I say. ‘I want things to go back to normal.’

Dad makes a ‘hmph’ sound.

‘Maddie, this way you won’t get a criminal record,’ Jay says. ‘We could ask for a fine, but if we do that, it’ll be over, sure, but there will be a record. Is that what you want?’

‘I didn’t know any of this would happen,’ I say.

‘No,’ Jay says. ‘People usually don’t think. Until it’s too late.’

Her voice is kind, but her words make me want to cry.

‘Okay,’ I say. ‘I’ll go on the program.’

‘All right,’ Jay says. ‘Are you ready to go into court now?’

I swallow. ‘I guess,’ I say.

‘Come with me,’ Jay says, standing up and slipping on a black jacket. She indicates for Dad and me to leave the office. The door closes with a bang. I walk alone, behind Jay and Dad. Dad is asking questions in a low voice, and Jay is answering.

I can’t believe this is happening. It is as if I am in a virtual reality game, and any moment, I’ll look up and find myself back in regular life, doing regular things. But I can’t turn off what is happening, no matter how hard I wish it.

And I have nobody to blame but myself.

When we walk into court, it is silent, the way a class is during silent reading, the quiet of a lot of people concentrating. Dad and I copy Jay’s nod at the magistrate at the door, then stand there, paused. At the back of the courtroom are two long lines of chairs, where adults are sitting, staring straight ahead, or rifling through their papers. Here and there young people are perched, waiting: I am too scared to look at them directly. In the middle are desks with tall microphones like xylophone sticks, and stands for people to put their papers on. Above them all, on a raised platform, surrounded by an enormous desk, is the magistrate. The ceiling slopes from low near the lines of seats to high above the magistrate. Behind the magistrate’s desk stretches a long narrow window, framing the blue sky that exists outside the court, the blue of a freedom that doesn’t exist inside it. The air is stuffy and I wish I wasn’t wearing the long sleeves and tight collar of the dress Dad bought.

‘There,’ Jay whispers, pointing to two vacant seats at the back, for Dad and me.

I lower myself onto the seat, shrinking away from the boy who is sitting on the other side. His legs are stuck out in front of him: there are blue tattoos snaking up his ankles, which disappear into the ironed trousers he wears. His fingers are drumming on his thighs.

Maddie in the Middle

Maddie in the Middle